Source: See How the Body Understands. See it Working: A review on Boy with Thorn by Rickey Laurentiis

He shut the thorn up in his foot, and told his foot / Walk

Rickey Laurentiis’, Boy with Thorn, is simply lovely. In this book, winner of 2014 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, Laurentiis addresses the countless brutalization and sexualization accounts in which black, queer bodies endure. In addition, he comments on visual arts in relation to black bodies, and the representation said art holds, using narrative and ekphrastic forms of poetry. Moreover, he allows personal thought to “interrupt” the poem, adding a well needed (and loved, if you asked me) layer to this subjects that we might not otherwise get. As a whole, Laurentiis is stating how the black body struggles with itself, and its understanding of itself. Is seeks to survive through questions, realizations, and art.

In the first section of the book, Laurentiis talks about roots, black bodies, and their relation to the queer black male and the violent acts against said communities. The book opens, rightfully so, with the poem, “Conditions for a Southern Gothic”:

Therefore, my head was kingless.

I was a head alone, moaning in a wet black field.

I was like any of those deserter slaves

whose graves are just the pikes raised for their heads, reshackled, blue

and plan as fear.

All night I whistled at a sky that mocked me,

that fluently changed its grammar as if to match desire in my eye.

My freedom is possible, it said.

As if my torn-off head in that bed swamped and whelming then

with water had one wish, and it did: to think stranger stuff,

to break that boring need to always have a shadow trail its maker, such that:

1. The shadow snaps, rising to kiss the head;

2. The kiss lands, the head flies up in airy revolt;

3. Cracked from the head come the crows of its thinking;

4. Three crows move in minstrelsy against the night;

5. And the head still singing: Last night, a Negro was axed . . .

Who among us was made to scratch a myth? Speak. If God made us in his image, it was the first failure of the imagination.

In this poem, we see a lot of Laurentiis’ tropes–imagery, narrative, personification, and others–to introduce to the book and his writing style. This piece comments on blackness and what it means to be black in America; how it correlates to blackness prior and presently. By taking on this role of being a slave, thus comparing his present blackness, to the violence black people endured, Laurentiis is allowing the reader into a hostile image. “I was a head alone, moaning in a wet black field. / I was like any of those deserter slaves / whose graves are just the pikes raised for their heads, reshackled, blue / and plain as fear” (Line 2-5). There is something jarring about comparing oneself to a staked head. Here, he is saying how stark blackness is, and how even present day, blackness is seen as a threat. Yet, as we get back to him in the field as a head (which is simply a beautiful and rendering image), the reader is again introduced to this notion of blackness as it relates to “freedom.” In line 8, the sky says, “My freedom is possible.” As the poem continues, we understand that there is a risk while this head is in thought–to break away from this track that has been set out; this cycle of blackness. Of queer-blackness. He ends this thought with a pointed finger at God, suggesting that his act of creating man was indeed a failure. A bold statement.

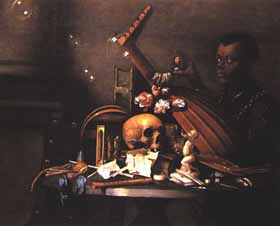

As this section continues, Laurentiis gives us similar poems addressing the black body and how it consistently undergoes violent and trauma. In “One Country,” the body wants a release of itself and its thirst. In “Vanitas with Negro Boy” he is giving the reader the actual painting, Vanitas with Negro Boy by David Bailly. However, in this piece, Laurentiis is inserting the black boy’s thoughts/questions (personified as himself), as well as commenting on this black boy in the voice of David Bailly. There are lines here, that really give us another insight to the portrayal of blackness/black bodies–“That / was the boy’s job, this cage with a debt / in it (And whose boy am I, and what is / my name?) There is something beautiful about how Laurentiis inhabits two bodies at once. In addition, this inhabitation allows the reader involve themselves in the duality of art and the layering of the poem. He addresses more than how black bodies are portrayed, but comments on how the black body questions itself. Furthermore, this poem realizes the beauty in the black body, and how it has to endure the gaze placed on itself through various forms of art and media.

As this section continues, Laurentiis gives us similar poems addressing the black body and how it consistently undergoes violent and trauma. In “One Country,” the body wants a release of itself and its thirst. In “Vanitas with Negro Boy” he is giving the reader the actual painting, Vanitas with Negro Boy by David Bailly. However, in this piece, Laurentiis is inserting the black boy’s thoughts/questions (personified as himself), as well as commenting on this black boy in the voice of David Bailly. There are lines here, that really give us another insight to the portrayal of blackness/black bodies–“That / was the boy’s job, this cage with a debt / in it (And whose boy am I, and what is / my name?) There is something beautiful about how Laurentiis inhabits two bodies at once. In addition, this inhabitation allows the reader involve themselves in the duality of art and the layering of the poem. He addresses more than how black bodies are portrayed, but comments on how the black body questions itself. Furthermore, this poem realizes the beauty in the black body, and how it has to endure the gaze placed on itself through various forms of art and media.

Of the Leaves That Have Fallen

Wallace Stevens, “Like Decorations in a Nigger Cemetery”

1.

In the imagination there is no daylight and,

Like Wallace Stevens, I know the dark is crucial.

I sing, I grieve in it, I dream what haunts each night:

These bodies, even lynched, still are thinking.

Nothing is final, I’m told. No man shall see the end—

But them, my fathers, lifted into fire, like tongues.

2.

To navigate the dark you must listen, you must listen

To the dark: the wind, a wind in the trees, the birds,

Birds shaping a sound around the green busyness in the trees.

3.

It was when he only called for mercy as in “God, O Take Me

Higher,” while vanishing, shut up in heat, his eyes and veins

Rupturing, that I knew the night was made for many kinds of desire.

(Read the rest here.)

The entire second section is Laurentiis’ one poem, “Of the Leaves That Have Fallen.” And it is completely brilliant. In this poem he is directly asking Wallace Stevens how he could write a poem, “Like Decorations in a Nigger Cemetery,” without commenting on blackness, black bodies, and the brutish acts towards both. In Stevens’ poem, death is meditated through imagery of the gruel landscape. Yet, there is a reference to the black body, seen in his title, but does not inquire or dive into the importance of the black body during this time. Laurentiis’ poem, directly comments on Stevens’ complete disregard for the black body. In addition, this piece evokes how this body is seen, attacked, and often overlooked. He even writes in the same exact form of Stevens, thus going through great lengths to correcting him. Moreover, this piece allows the reader into a conversation about history’s role in blackness by addressing specific accounts, such as, the Civil War and Emmett Till. The reader is understanding and welcomes a different outlook on blackness in direct comparison to how another poet disregards blackness.

The book ends with the third section addressing southerness and the history of blackness as it relates to such. It’s invigorating, actually, how Laurentiis completes this collection. In this section, we see how the black body is stretched and bruised. Also, there is a serene underlying tone in this section that we don’t necessarily see in the sections beforehand. In the poem, “A Southern Wild,” we see a young boy racing another boy to the top of a hill. Though the subject is simple, the commentary in the piece is rich–realizing the boy’s body in relation to the landscape and how much the body can handle. There are questions in this piece that further gives the reader insight on this constant inner battle.

The two poems in this section that can easily sum up the book are “You Are Not Christ” and “Take it Easy.” In “Take it Easy,” we are given this:

That the light stalks your skin,

no, that your skin makes it: a radiating

hum, jive, a freedom, a beehive

packed just as much with honey as does it

hazard; also, a balm for where the sting sits,

a treaty, country upon which I first

laid my claim, but was usurped; where

carefully do I move to cross it again. Now here

come my lips to it, pink over your body’s

good bark. Now here is my mouth, entire.

I’m scared of you, baby, it says, scared like a god

is of his faithful–and like the faithful. Light-

struck. Delighted. Terrorstruck. Come, lift up

your gates, your countenance spread like a lily upon me:

whip me, I am so whipped. These are my eyes.

Do you see it? How the black body responds to itself. How it understands.

-Luther Hughes

*Purchase Boy with Thorn here*